Straddling the Polish-Belarussian border in northeastern Poland, Białowieża Forest is the last of the vast primeval forest that once stretched across the European lowlands. Strictly protected for centuries by royalty as a private hunting ground, it is now a living museum of ancient natural processes replete with species extinct elsewhere.

Yet despite this special status, Polish government officials yesterday signed extensions to the State Forests’ logging quotas in the ancient woodland. In the face of intense criticism from NGOs and scientists, it argues this move is essential to maintain public safety and ‘actively conserve nature’. This heralds the latest episode in a long running dispute between the EU and Poland over its management of the Natura 2000 protected area. In 2018 the European Court of Justice ruled that Poland had failed to ensure sufficient protection of key species and habitats in the forest.

The latest logging plans apply to two out of Białowieża Forest’s three forest districts. In plans they say are essential for implementing the 2018 European court judgement, the state forestry corporation will log around 19,000 m3 of wood by the year’s end. An even larger quota for logging the forest’s third district was left unsigned, apparently due to the European Commission’s objections, which environmentalists claimed as a partial victory in their battle to stop the logging.

Although the plans spare the forest’s best-preserved tree stands, classed as those over 100 years, scientists say the cuttings will devastate areas important for conserving biodiversity. Foresters are to fell large tracts of only slightly younger tree stands, of ca. 90 years of age. The state forest company argues these areas are fair game for logging, as they are of poor conservation value, having been previously logged in the early 20th century. During this time, vast areas of untouched primeval forest were clear-cut and devastated – by German occupants during WW1, and again during the interwar period by a British company, the Century European Timber Corporation.

The State Forests say it is now their legal duty to remedy this historical damage by ‘reconstructing’ the forest with a more appropriate mix of tree species. This entails cutting and selling the existing trees, and planting new ones in their place.

But scientists point out that this misses a key point. Many of the areas now targeted for logging are natural secondary growth; these are not plantations of little conservation value. These are areas that have regenerated naturally over the past 90-100 years, and have returned to nature, hosting many endangered species.

Client Earth, an environmental law charity, wrote on its website that the increased logging quotas are based on inadequate forest inventories that supress the abundances of protected species. Moreover, contrary to the claims of the State Forests, the loggings will in fact be carried out in the most valuable old-growth stands over 100 years old.

A second argument for the loggings is that large quantities of standing dead wood near communication routes pose a danger to public safety. But opponents of the logging plans point out that this can be remedied by cutting the standing trees and leaving them in place to decompose. However, rather than be left to provide habitat for a variety of protected species, the State Forests insist this wood should be used to supply locals with firewood to heat their homes.

The latest forest management plan puts an end to the what have perhaps been the most peaceful three years in Białowieża Forest’s recent history. Prior to 1915, the forest was strictly protected for centuries. But since the historical system of protection broke down during WW1, logging has been ever present on the Polish side of the forest. That’s until the 2017 European Court of Justice ruling that ordered foresters to halt all forestry activities. Since then, foresters have been laying low. The only trees cut during this period have been for safety reasons; for the first time in a century, the forest has been governed by nature, and not the foresters saw. With the signing of the latest annexes to the forest management plans, this brief respite is coming to an end.

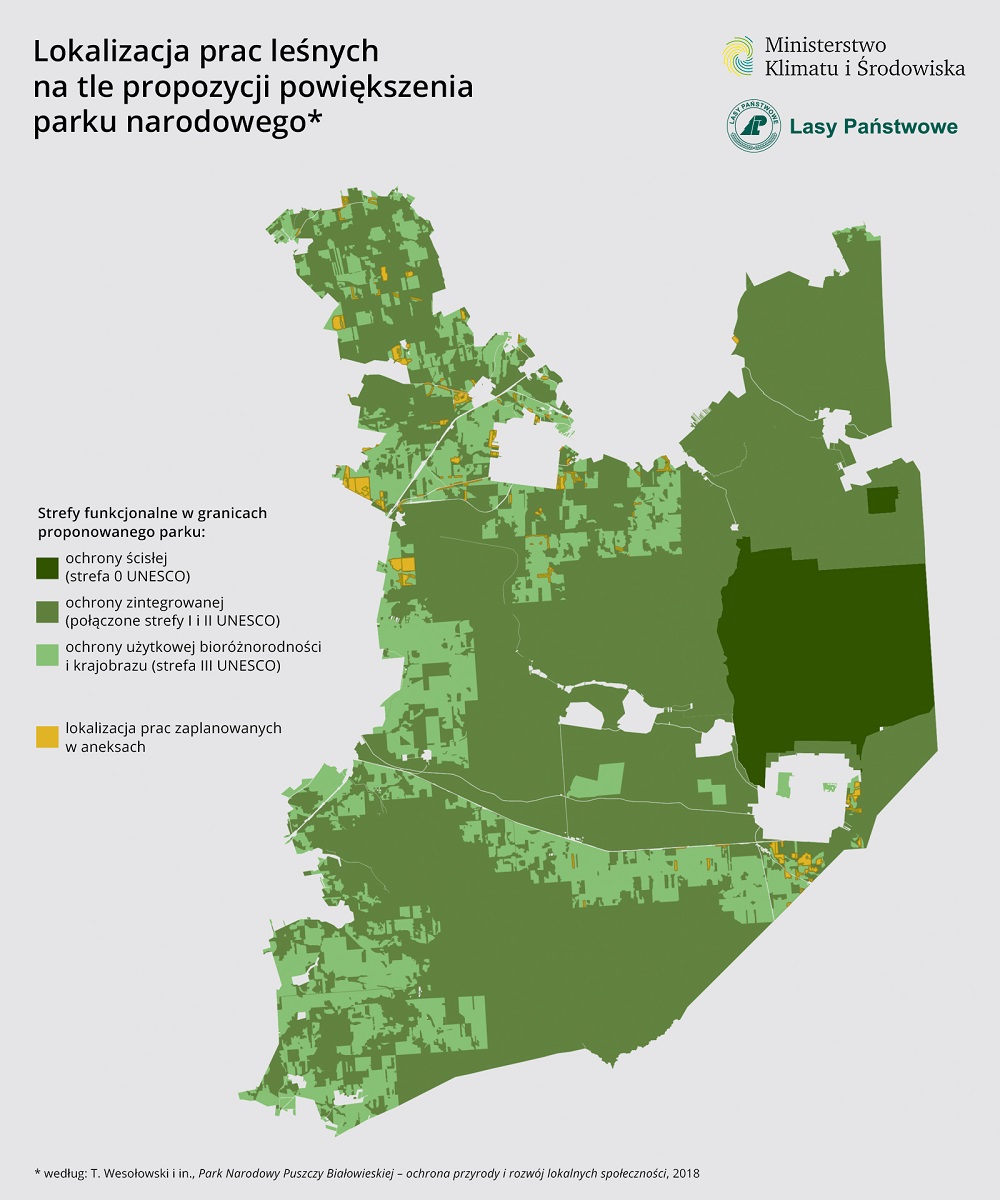

A perpetual state of inadequate legal protection is what allows Europe’s best-preserved natural forest to regularly be logged. Only 18% of the Polish side of the forest is protected as a national park (where logging is banned), with the rest under the jurisdiction of the State Forests, whose primary objective is to make profits from selling wood. For many years a coalition of activists and scientists has campaigned to extend the national park over the whole area of forest on the Polish side of the border. Belarus by contrast protects the entirety of its part of the forest within a national park.

As in 2017, again it seems like the forest’s last hope lies with the European Commission. Polish law makes no provisions for its citizens to petition a domestic court to review a forest management plan. The only institutions capable of reversing the decision are the Polish government itself, or the European Court of Justice, which is notoriously slow to act.

However, this time around the Commission has moved quickly. In its February infringements package, it sent a letter of formal notice to Poland for failing to ‘implement measures which would preserve the integrity of the site, ensure conservation and protect the species and habitats [….] Poland has two months to remedy the situation otherwise the Commission may refer the case back to the Court of Justice of the EU with proposed financial sanctions’.

With the State Forests promising not to begin logging until the end of the bird breeding season in September, the EC now has a brief window to save the forest from further destructive logging.

Pingback:Variety is our world’s spice – History is the best story